Indian Burning, The Myth of the Humanized Landscape and Parks and Wilderness

The idea that frequent low severity blazes as was practiced by some tribal people can reduce large conflagrations is widely promoted by the media, timber industry, tribal people, and social justice groups. Photo George Wuerthner

When reporting about wildfires, few media articles fail to claim that frequent burning by tribal people reduced fuels, resulting in few high severity fires. Indian burning is extolled as a panacea that if widely adopted will preclude or at least significantly reduce the large blazes the West is experiencing. [i] [ii]

Supporters of promoting Indian burning are diverse but can be generally categorized into three groups: Timber industry advocates, Anthropocene boosters, and social justice promoters, particularly those among the social justice movement concerned with the past abuses of tribal people.

To the degree that Indian burning may have influenced the landscape, it was limited to specific plant communities, and in general, was not a landscape influence across the continent. Missing from any of their discussions is any sense that humans may not have the wisdom or knowledge to manipulate or manage the entire planet.

INDIAN BURNING WAS PRIMARILY LOCALIZED

Anthropocene boosters frequently use Indian burning as one of the major pieces of evidence to support their contentions that there is no such thing as wildlands nor any part of the planet that wasn’t under human control.[iii] But such pronouncements fail to consider the variability in human influence on both temporal and spatial scales.

There are some researchers who support the contention that Indian burning had widespread influences. However, most of these studies were done near Indian settlements where no doubt burning was frequent, but then are inappropriately extrapolated to the larger landscape. [iv][v]

There is evidence that tribal people often burned the local landscape near their settlements, but whether this influenced the wider landscape is debated. Photo George Wuerthner

As Barrett et al. 2005 noted: “For many years, the importance of fire use by American Indians in altering North American ecosystems was underappreciated or ignored. Now, there seems to be an opposite trend… It is common now to read or hear statements to the effect that American Indians fired landscapes everywhere and all the time, so there is no such thing as a ‘natural’ ecosystem.”

A myth of human manipulation everywhere in pre-Columbus America is replacing the equally erroneous myth of a totally pristine wilderness.

We believe that it is time to deflate the rapidly spreading myth that American Indians altered all landscapes by means of fire. In short, we believe that the case for landscape-level fire use by American Indians has been dramatically overstated and over extrapolated.”

Other scientific studies support this contention. For instance, Whitlock and Knox did a study of Oregon’s Willamette Valley which had one of the highest pre-European native populations in North America. If Indian burning was a major influence on landscapes, one would expect to find evidence there.

The mild and productive Willamette Valley of Oregon had one of the highest populations of tribal people in North America, however, the evidence that Indian burning significantly increased the frequency and landscape effect of wildfire is contested. Photo George Wuerthner

Yet, regarding Indigenous ignitions in the Willamette Valley, Cathy Whitlock notes: “The idea that Native Americans burned from one end of the valley to the other is not supported by our data … Most fires seem to have been fairly localized, and broad changes in fire activity seem to track large-scale variations in climate” (Fire Science 2010).

In a charcoal study of Washington’s Battle Ground Lake, Megan Walsh (Walsh et al. 2008) concluded that fire frequency was highest during the middle Holocene when oak savanna and prairie were widespread near Battle Ground Lake. She suggests: “The vegetation and fire conditions were most likely the result of warmer and drier conditions compared with the present, not from human use of fire” (Fire Science 2010).

The Rogue River in the Klamath Siskiyou region of Oregon and California. Research here suggests climate/weather was the primary agent for wildfire occurence and spread. Photo George Wuerthner

Colombaroil and Gavin (2002) documented that large fires always occurred in the Siskiyou Mountains of northern California and southern Oregon, primarily due to climate/weather, even during the pre-European period. “Fire is a primary mode of natural disturbance in the forests of the Pacific Northwest. Increased fuel loads following fire suppression and the occurrence of several large and severe fires have led to the perception that in many areas there is a greatly increased risk of high-severity fire compared with presettlement forests. To reconstruct the variability of the fire regime in the Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon, we analyzed a 10-m, 2,000-y sediment core for charcoal, pollen, and sedimentological data. The record reveals a highly episodic pattern of fire in which 77% of the 68 charcoal peaks were before Euro-American settlement…”

T. Burcham analyzed diaries of Spanish explorers and British trappers who traveled through California before the American conquest in 1846. He concluded that Native American burning was not practiced throughout California and that the prehistoric forest landscape was not greatly different from the old-growth forest of his day.

His viewpoint is supported by many diaries and reports, ranging in time from John Charles Fremont’s second and third expeditions (1843-1846) to William Brewers account of the first California geological survey (1861-1864). Many overland travelers to California kept diaries during the Gold Rush period (1848-1855) and later years resulting in hundreds of descriptions of forests, wildlife, and scenery. Most of these accounts came from the gold country in the Sierra north of the American River, the foothills and lower mountain slopes of the central Sierra as far south as Mariposa, and the Klamath and Trinity Rivers.

The idea that forests were uniformly open and park-like due to frequent burning is not supported by many historical accounts. Granite Chief Wilderness, Tahoe National Forest, California. Photo George Wuerthner

These accounts most often described forest conditions as “dark,” “dense,” or “thick,” rather than “open” or “park like.” Perhaps the best description by a forty-niner was by J. Goldsborough Bruff, who traveled the western slopes of the Feather River drainage between 1849 and 1851. He kept a detailed diary and clearly distinguished between open and dense forest conditions. He recorded the latter six times more often than the former.

One thread common to most accounts was awe at the immensity and grandeur of the trees in the forest, especially the sugar pines. Accounts by the first explorers of the upper slopes of the central Sierra and southern Sierra reported more open forests than in the north, but brush and smaller trees were often found under the large trees. John Muir described open forests of ponderosa pine but also found brush and small trees to be an integral part of most of the central and southern Sierra forests he traversed in the period 1869-1875.[vi]

In yet another study, Vachula et al. (2019) reviewed the fire history of what is now Yosemite National Park where, historically, large Indigenous communities resided. Their research found a direct correlation between climate and the amount of burning on the landscape.

While Indian burning near settlements in the Yosemite Valley likely had an influence on fire regimes, climate still largely influenced fire at local and regional scales. Photo George Wuerthner

“We analyzed charcoal preserved in lake sediments from Yosemite National Park and spanning the last 1400 years to reconstruct local and regional area burned. Warm and dry climates promoted burning at both local and regional scales…

Regional area burned peaked during the Medieval Climate Anomaly and declined during the last millennium, as climate became cooler and wetter and Native American burning declined.

Our record indicates that (1) climate changes influenced burning at all spatial scales, (2) Native American influences appear to have been limited to local scales, but (3) high Miwok populations resulted in fire even during periods of climate conditions unfavorable to fires. However, at the regional scale (< 150 km from the lake), fire was generally controlled by the top-down influence of climate.” (Vachula et al. 2019) Geographer, Thomas Vale came to similar conclusions (Vale, 2002).

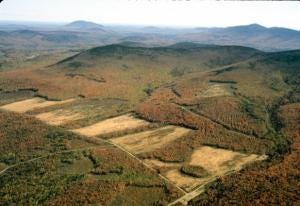

These findings are not limited to the West. David Foster who has studied historic land use in New England came to a similar conclusion: “Our study contradicts the theory that people had significant ecological impacts in southern New England before European arrival. Instead, it reveals that old forests, shaped by climate change and natural processes, prevailed across the region for thousands of years.”1

And these findings are not unique to North America. A recent study looking at a 5000 record of fire in Peru found: “The extent to which pre-Columbian societies in Amazonia occupied and significantly altered the tierra firme (nonflooded, nonriverine) forest environment is an enduring question and the subject of a current debate. Our research addresses these issues in tierra firme forests of northeastern Peru. We present phytolith and charcoal data indicating the forests were not cleared, farmed, or otherwise significantly altered in prehistory.”[vii]

EVOLUTIONARY EVIDENCE

Although there are numerous scientific studies that document the limited influence of Indian burning, there is also evolutionary evidence for this in our plant and animal communities. If Indian burning influence was as widespread as suggested, many common species would be rare. For instance, Sitka spruce is found along the coasts of California to Alaska. The species has no adaptations to fire, and if Indian burning were widespread along the coast, Sitka spruce would be relatively uncommon. Same the for chaparral, which is not adapted to frequent fire.[viii]

Though many tribal people lived in the low elevation sagebrush steppe, there is little evolutionary evidence that they influenced fire regimes. Sagebrush has no adaptations for surviving frequent fires. Photo George Wuerthner

Similarly, sagebrush has few adaptations to fire. Depending on the species of sage, fire rotations sometimes exceed 400 years. Because burning was historically infrequent in sagebrush ecosystems, it was once one of the more common plant communities across what is known as the sagebrush steppe. Numerous wildlife species from sage grouse to sage thrasher to pygmy rabbit have all evolved to utilize the sagebrush ecosystem. Again, if fires were as frequent and widespread as asserted by proponents, we would not find extensive regions of sagebrush, nor wildlife like the sage grouse.

It is a false sense of equivalency to suggest human influence was equal across the planet. Any rational person would acknowledge that there are humans living in the Los Angeles Basin in California and the Arctic slope of Alaska but recognize that the degree of human manipulation of both locations is not equal.

The scientific evidence suggests that Indian burning was localized, and not a landscape influence. There were and still are many natural ignition sources, primarily lightning which is sufficient to maintain natural fire regimes on the landscape.[ix]

To the degree that Indian burning was additive (in other words, charred more acres), one could argue it imposes an artificial fire regime upon plant communities that would not exist under natural conditions.

HIGH SEVERITY FIRES CREATE WILDLIFE HABITAT

The snag forests that result from high severity blazes is one of the most transient, yet important wildlife habitat for many species of plants and animals. Photo George Wuerthner

Another problem with the current rage of promoting Indian burning as a panacea for high-severity fires is that it devalues the ecological importance of resulting snag forests which create wildlife habitat for more species than low-severity blazes. For instance, we find greater numbers of flower species, more mushroom species, more bees and butterflies, more bat species, more birds, and even more fish in areas influenced by high-severity fires. This is evolutionary evidence for the prior existence of high-severity burns on the landscape.

Similarly, many plant communities like sagebrush have no adaptation to frequent fire. If you burn sagebrush every few years, it disappears from the site and is typically replaced by grasses. Same for chaparral. Yet the fact that we have species like sage grouse, sage sparrow, sage thrashers, pygmy rabbits, and a host of other sagebrush-dependent species suggests a long period where frequent fire was not a major influence on the landscape.

Indeed, the idea that Indian burning was a widespread influence on the landscape has been challenged by numerous studies. To the degree Indian burning had any effect, it was primarily localized.

Logging of lodgepole pine forest near Redfish Lake on the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, Idaho. Lodgepole pine has a naturally long fire rotation of hundreds of year, and tends to only burn during periods of severe drought. This is evidence that frequent low severity burning by tribal people did not extensively influence this plant community. Photo George Wuerthner

Again, we have evolutionary evidence because most higher elevation forests have long fire rotations that typically exceed hundreds of years. These forests are not adapted to frequent fires.

HOW DID FORESTS SURVIVE BEFORE HUMANS?

Given this evidence why do we hear so frequently the assertion that Indians as “caretakers” of the land and that without Indian burning somehow our forests were and are somehow “unhealthy.”

Since Paleo Indians only colonized North America at most 15,000-18,000 years ago, depending on whose study you accept (slightly older dates are more contested), it means that all the major plant communities on the continent existed for millions of years without any human influences.

All major plant communities like this spruce dominated forest in Colorado existed long before any humans colonized North America to influence fire regimes. One could argue that Indian burning to the degree it influenced any plant communities altered the natural evolutionary fire rotations. Photo George Wuerthner

So, Indian caretaking as exemplified by frequent low-severity human ignitions, if they were as widespread and ecologically influential as proponents assert, is a relatively recent (in geological and evolutionary timescales) influence on plant communities that disrupts natural fire regimes.

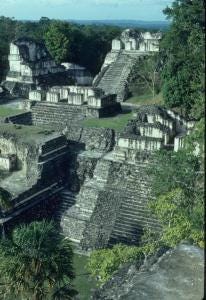

Evidence exists that clearing of tropical forests for agricultural production led to the demise of the Mayan culture in Central America. Photo George Wuerthner

The same thing could be said for forest clearing. Evidence that the Mayan Indians in Central America cut and burned a large swath of tropical jungle for corn production[x], the documented overcutting of juniper forests by Anasazi around their cliff dwellings,[xi] and the slash and burn agriculture practiced in many locations from the East Coast to Central America are consistent with creating “healthy” forests.

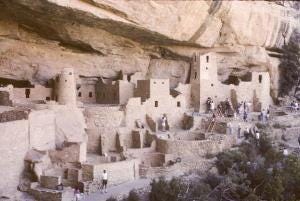

There is evidence that localized over cutting of forests led to increasd erosion and arroya cutting that exacerbated the extenstive drought, contributing to the demise of the cliff dwelling people of the Southwest. Photo George Wuerthner

The idea that there is “wisdom” in such “traditional knowledge,” such as setting fires belies that these activities were frequently destructive, not beneficial to many species and ecological functions.

Furthermore, they are not unique to North American tribal people as evidence exists showing that people in northern Europe 20,000 years ago were burning forests as well. [xii]

WHY IS INDIAN BURNING CELEBRATED?

So why do we hear so much about Indian burning? I don’t presume to know what is inside people’s minds or their motivations, but here are a couple of ideas to consider.

Clearcuts in Maine. Not often seen as allies, but both the timber industry and some in the social justice movement the idea that humans have always modified the landscape and thus is used to justify landscape scale manipulation today. Photo George Wuerthner

For the timber industry and its allies, arguing that Indians modified great swaths of the landscape provides a philosophical and flawed ecological justification for human manipulation of the Earth.[xiii] The Industrial Forest Paradigm equates green forests with “healthy forests” because green trees make better lumber. Frequent burning, we are told, will result in fewer high-severity fires, so we must follow the “wisdom” of the first colonists and promote green forests by various measures, including more prescribed burning as well as thinning/logging.

There is a tendency to promote the idea that tribal people around the globe were and still are the “ultimate caretakers” of the planet. Photo George Wuerthner

A second rationale for promoting Indian burning comes from the political sector – the social justice movement. There is a growing tendency to promote Indians as the ultimate “caretakers” of the land. It is part of the myth that Indian people lived in “harmony” with the planet because of genetics or culture.

Much of this trend is part of a political agenda that sees conservation strategies like parks, wilderness reserves, and other nature protection as contrary to social justice.[xiv]

Social justice organizations sometimes characterize national parks and other conservation reserves as examples of “colonialism” and advocate transfer of public lands to tribal people. George Wuerthner

Many in the social justice movement attack conservation and nature protection ideas like preserving Half the Earth[xv] as colonialism, imperialism, and cultural genocide. The establishment of parks and other nature preserves are deemed “fortress conservation.” [xvi]Critics of parks, wilderness, and other nature reserves argue that disadvantaged people bear the brunt of conservation efforts.

At least for some, the goal of this ongoing critique from academic disciplines like anthropology, cultural geography, and history, is to provide a philosophical and even a legal basis for the transfer of public land to tribal people, [xvii]or at a minimum give greater control over public lands as if it would “fix” the ecological crisis we face due to extensive overdevelopment. [xviii][xix]

This perspective ignores the fact that low population and low technology could account for the lower physical footprint of all tribal people around the globe. This includes the ancestors of Europeans, Asians, Africans, and the original Indian colonizers of North and South America.

There is evidence that once tribes acquired the horse and gun, Indian hunting of bison may have contributed to the demise of bison on the plains. Photo George Wuerthner

There is plenty of evidence that tribal people, even with limited technology and low population, were capable of destructive behavior. The plains Indians likely contributed to the demise of the great bison herds once they acquired the horse and rifle.[xx] Numerous other examples of native overexploitation include the extermination of nearly 2,000 bird species by Polynesians[xxi] or the demise of Ice Age mammals, at least in part attributed to overhunting by Paleo Indians. [xxii] Elk were diminished in California by Pre-European Indian hunting.[xxiii]

There is abundant evidence that strictly protected areas work to protect biodiversity if sufficiently large enough and well-funded.[xxiv][xxv]

Globally research demonstrates that strictly protected areas are the best way to preserve biodiversity and ecological function. Kluane National Park, Yukon Territory, Canada Photo George Wuerthner

A third possible explanation is a human insecurity. Many people fear Nature and want to control and dominate the natural world, whether it is tribal people who feared natural phenomena and gods who had to be appeased through ritual, sacrifices, and sorcery, to ranchers who kill predators to protect their livestock, or farmers that wish to control insects with pesticides to safeguard their crops. We also seek to minimize the unpredictable and unknown forces that can harm humans.

Even where such endeavors don’t work, the appearance of control of natural forces provides some security in a world that seems to have no particular care for the human endeavor.

If viewed from an evolutionary perspective, Indian burning and other manipulations of natural landscapes are part of the problem. The attitude that humans should and must manipulate the planet is the primary philosophical reason we have an environmental crisis. When our population was low and technology limited, human influence was primarily localized – it is now global.

Cropland in California’s Central Valley has nearly eliminated the natural landscape. Without parks and preserve, there would be few places left for native wildlife and plants. Photo George Wuerthner

However, with nearly 8 billion people on the planet, we can’t help but manipulate large swaths of the Earth to survive. But we should not view such manipulation as beneficial to the earth and most of its creatures; instead, we should acknowledge that humans have a disproportionate ecological footprint.

With nearly 8 billion people, humans have a dispropotionate impact on the planet. Nature requires parts of the planet where the human control and manipulation is minimized. Photo George Wuerthner

Parks and wilderness reserves and other “self-willed” landscapes embody a philosophical attitude that counters human arrogance and dominance. These protected landscapes represent areas where we relinquish, to varying degrees, control and allow natural processes to operate with minimum interference by humans. Without creating parks, wilderness, and other nature preserves, our impact on the planet would only be greater, and ultimately more destructive. [xxvi]

[i][i] https://www.vox.com/21507802/wildfire-2020-california-indigenous-native-american-indian-controlled-burn-fire

[ii] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/21/wildfire-prescribed-burns-california-native-americans

[iii] https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/870991

[iv] Anna Klimaszewski-Patterson, Peter J. Weisberg, Scott A. Mensing & Robert

Scheller 2018 Using Paleolandscape Modeling to Investigate the Impact of Native American–Set Fires on Pre-

Columbian Forests in the Southern Sierra Nevada, California, USA

[v] Zybach, Robert. The great fires : Indian burning and catastrophic forest fire patterns of the Oregon Coast Range, 1491-1951

[vi] Cermack, Robert, 2005. A history of fire control in California National Forests. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/6002574

[vii] Pipernoa, Dolores R., Crystal H. McMichaelc, Nigel C. A. Pitmand, Juan Ernesto Guevara Andinod, Marcos Ríos Paredesd, Britte M. Heijinkc, and Luis A. Torres-Montenegro. 2021. A 5,000-year vegetation and fire history for tierra firme forests in the Medio Putumayo-Algodón watersheds, northeastern Peru. PNAS October 5, 2021 118 (40) e2022213118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022213118

[viii] https://www.californiachaparral.org/fire/native-americans/

[ix] https://rewilding.org/indian-burning-myth-and-realities/

[x] https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/77060/mayan-deforestation-and-drought

[xi] https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Long-Term-Anasazi-Land-Use-and-Forest-Reduction%3A-A-Kohler-Matthews/4010961cd1a44b3391e6694c77cf43d556e08412

[xii] https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/12/161201092823.htm

[xiii] https://www.pnas.org/content/118/17/e2023483118

[xiv] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/oryx/article/halfearth-or-whole-earth-radical-ideas-for-conservation-and-their-implications/C62CCE8DA34480A048468EE39DF2BD05

[xv] WILSON, E.O. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. Liveright

Publishing, London, UK.

[xvi] http://outsideinradio.org/shows/fortressconservation

[xvii] https://indiancountrytoday.com/news/historic-meeting-renews-push-for-black-hills

[xviii] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/05/return-the-national-parks-to-the-tribes/618395/

[xix] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/03/magazine/california-widfires.html

[xx] http://www.thewildlifenews.com/2021/06/01/indian-culpability-in-bison-demise/

[xxi] Adam Nicolson The Seabird’s Cry: The Lives and Loves of Puffins, Gannets and Other Ocean Voyagers

London: William Collins, 2017 p.273

[xxii] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277379121005230?via%3Dihub#!

[xxiii]https://www.academia.edu/6830804/Late_Holocene_Resource_Intensification_in_the_Sacramento_Valley_California_The_Vertebrate_Evidence

[xxiv] https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/01/220127120156.htm

[xxv] WUERTHNER, G., CRIST, E. & BUTLER, T. (eds) (2016) Protecting the

Wild: Parks and Wilderness, The Foundation for Conservation.

Island Press, London, UK.